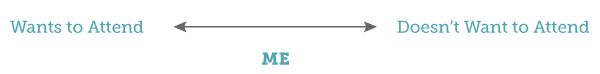

Often when we ask a question, the answer that comes back is a bit perplexing. We ask the child who is not attending school if he wants to attend, and he says “yes.” We ask a child who continually gets in trouble, if he wants to be in trouble, and he says “No.” The confusing part is that the answer given is, to some extent, true, but also untrue. The words say one thing; the behaviour– school refusal, aggressive behaviour, etc, says something else. I find it very useful in these instances to phrase the question like this– This is obviously a complicated situation for you. Clearly part of you wants to go to school and part of you doesn’t. Let’s graph it. Show me on this line how much of you wants to attend and how much of you doesn’t.

The graph above shows the most severe form of ambivalence, the place of most discomfort—stuck right in the middle. This is paralysis! You move a little to the left and then the right pulls you back; a little to the right and the left pulls at you. If you can move to 60% on one side you can begin to act a bit. I recently posed this way of looking at things to an adolescent boy, 15 years old, who had been staying home from school for 1 ½ years and really suffering about it. He introduced a new very clever addition to the concept. His graph looked like this:

![]()

Oh the power of defense mechanisms! He got so tired of experiencing the debilitating anguish of ambivalence that he introduced a buffer zone, an “I don’t care” zone that he thought he could hide out in when he got tired of going back and forth between the other two options. This ultimately doesn’t work, because the “I don’t care” zone is not the dominant zone and he still finds himself going back and forth too often between wanting and not wanting to attend school. The mind has a lot of clever tricks.

I offered him this alternative—It’s important to get out debilitating ambivalence and not just by playing mental tricks. You choose one side to be on. I suggested that if he could go to school, he would already have done so. So let’s choose “staying home.” He has to decide to stay home and do his best to make “staying home” work for him. Really try to have good days at home. Create a schedule that he likes and see if staying home is a viable alternative. If he gives it his all, then there will be two options. After a few months he will either like his life of staying home and he can continue down that path without any regret, or he can say “Well, I tried that. I really gave it my all and it didn’t work too well.” I need to try the other alternative, which is to go back to school.

This approach can be applied to many life situations where one finds oneself in a state of suffering caused by ambivalence—whether to leave a marriage, whether to leave a job, whether to quit the team, etc. If you try it, let me know how it works out.